Solar Industry FAQ

Updated August 2023

-

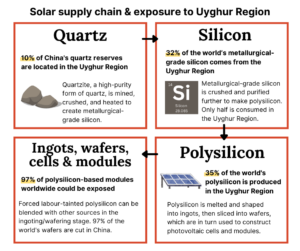

As of 2021, the four leading polysilicon manufacturers in the Uyghur Region are estimated to account for 48% of the world’s polysilicon production. All four openly admit participating in “labour transfer” programmes that experts agree are forced labour under international law. As of 2022, 35% of the world’s polysilicon and 32% of metallurgical-grade silicon are produced in the Uyghur Region.

Further, every level of the solar panel supply chain is exposed to Uyghur forced labour, from sourcing of raw materials to the production of polysilicon, ingots, wafers, cells, and modules (see infographic below). This is because mining, processing, and production within the solar supply chain, including quartzite mining, metallurgical-grade silicon smelting, and solar-grade polysilicon production, is concentrated in the Uyghur Region, which has pervasive links to forced labour and abuses that, according to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, may constitute crimes against humanity.

Solar-grade polysilicon is turned into ingots which are sliced into wafers. 97% of wafer manufacturing is done in China, further increasing the exposure of solar panels manufactured globally to Uyghur forced labour. Some of the world’s largest solar module manufacturers operating in the Uyghur Region reportedly use forced labour, source from polysilicon suppliers that are engaged in state-managed labour transfers, and have connections to the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), the Chinese government’s state-run paramilitary corporate conglomerate. The XPCC controls large mining and manufacturing operations in the region and has been included among entities under Magnitsky sanctions, and is listed on the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) entity list in the U.S. The Xinjiang Public Security Bureau, a state-run organisation responsible for security and policing in areas administered by the XPCC, was also sanctioned by the UK, Canada, EU, and U.S. for serious human rights violations taking place against Uyghurs and other ethnic groups in the Uyghur Region, in a move coordinated by the international community.

Overall, 97% of all polysilicon-based solar panels globally are at risk of exposure to Uyghur forced labour, based on research which assessed the supply chains of the global solar industry.

*This graphic, produced by the Coalition to End Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region, is solely representative of select inputs in the solar panel supply chain from the Uyghur Region and is not intended to be comprehensive.

-

Solar companies all along the supply chain – from solar panel manufacturers to polysilicon producers to raw material mining – have been reported to either directly use Uyghur forced labour or have Uyghur forced labour in their supply chains. Exposure to Uyghur forced labour also extends to stakeholders including solar installers, project developers, and investors of solar companies and projects.

-

In short, yes. Urgent action on climate issues and human rights go hand-in-hand. The transition to clean energy is imperative; however, a just transition cannot rely on products made in whole or in part with forced labour. Indeed, shining a light on human rights violations in the Uyghur Region has accelerated the development and diversification of solar supply chains inside and outside of China, creating an environment which more rapidly meets climate goals and creating more sustainable and resilient value chains.

Further, 100% of energy-intensive polysilicon production in the Uyghur Region uses coal-based energy. The use of fossil fuels in the production of solar panels results in high carbon emissions. The practice hinders the very objectives of the solar industry to provide clean energy to combat the climate crisis.

As long as the Chinese government continues the persecution of Uyghurs, the solar industry must not source from the Uyghur Region or from suppliers implicated in forced labour. The industry must be at the centre of the just transition and prevent the reliance on forced labour and fossil fuels in the production and processing of critical minerals and materials.

-

Forced labour is illegal and prohibited by international and national laws. Legislation aimed to control the trade and retail of products made with forced labour, such as the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, has demonstrated how import bans can be used to prevent tainted goods from entering the market. Thousands of shipments of solar panels have been stopped and scrutinised at the U.S. border under this law since its implementation. An import ban for goods made with forced labour is in place in Canada and a comparable trade and market ban has been proposed in the European Union. There are efforts towards their introduction by NGOs and parliamentarians in the UK and Australia with specific provisions made for goods made with Uyghur forced labour.

Mandatory due diligence laws in numerous jurisdictions are placing legal obligations on companies to meaningfully address forced labour in their supply chains. Strategic litigation is using national criminal laws in novel ways to target the proceeds from the sale of goods used with forced labour, which could give rise to criminal liability for companies that knowingly import such goods.

Investors are increasingly addressing this issue in their own portfolios, including divestment options, to mitigate risk from exposure to Uyghur forced labour and promote their commitment to Environmental, Social, and Governance priorities. Furthermore, sustainable investment portfolios that invest in companies linked to Uyghur forced labour risk being downgraded. Coordinated engagement by investors, led by civil society, is also happening across sectors.

-

Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, all companies are expected to conduct effective human rights due diligence to ensure that they are not causing, contributing, or linked to human rights abuses through their direct or indirect actions. This includes identifying where human rights are most at risk in their direct operations or supply chain relationships. Where human rights harms cannot be mitigated, prevented, or ceased, steps need to be taken to end business relationships responsibly.

Call to Action: As a first step, solar companies should complete a mapping of their value chain (including both upstream suppliers and downstream distributors, customers, and users) to identify direct and indirect business relationships that are connected to the Uyghur Region. Companies should then demonstrate steps to disengage from business relationships connected with forced labour in and from the Uyghur Region. Companies should publicly disclose these efforts and progress, including how they are working with affected rights holders or their credible representatives to consult on the steps they are taking. Companies with global sourcing operations should apply a single global standard across their supply chains in line with the requirements set forth in the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act.

Audits and certification programs are not viable, nor credible, in the Uyghur Region as access to the Uyghur Region to conduct due diligence is a practical impossibility, and information is restricted, opaque, or can be otherwise unreliable. Ending the solar industry’s dependence on the Uyghur Region could disrupt solar supply chains in the short-term. However, low-cost polysilicon production in the Uyghur Region is the result of forced labour and cheap coal-based energy in production of raw materials. As such, the industry is not only unethical but it is also unsustainable. As long as the forced labour system continues, the sector must act to establish production capacity elsewhere, or develop alternatives to polysilicon, which will result in a more innovative, diverse, and sustainable industry long-term while maintaining the affordability of solar energy.

-

The world’s polysilicon supply outside the Uyghur Region comes from elsewhere in China (30%) and other countries (25%), and alternatives both within and outside China are expanding rapidly. Alternative sources of polysilicon, as well as alternatives to polysilicon-based solar panels, will ultimately require innovation, collaboration, financing, and transparency by a broad group of stakeholders including, but not limited to, the solar industry, governments, and investors. This must be undertaken while putting pressure on the Chinese government to end its persecution of and restore freedoms to Uyghurs and Turkic and Muslim-majority peoples, and adopt fair labour and environmental standards.

Furthermore, the International Energy Agency warned that there are risks posed by having so few facilities providing sizeable global production, such as with polysilicon. One in seven solar panels produced worldwide is manufactured by a single facility, a level of concentration that represents a considerable vulnerability for the industry. The need to eliminate reliance on such a narrow number of suppliers is being addressed among policymakers in various countries.

Securing more ethical and stable supply chains that are critical to the renewable energy transition is an urgent priority for governments. The onshoring or friendshoring of raw materials is currently being considered in the UK, the European Union and the U.S. A diversified solar supply chain spread out across many countries will be more resilient to unpredictable disruptions such as economic or geopolitical volatility. Such efforts must not benefit or be developed solely by the U.S., UK, or Europe, but ensure that lower income countries have equal access to, and benefit from more diverse, stable supply chains, in order to support the urgent need for a global transition to clean energy.

-

Bifurcation refers to a scenario where a company has two parallel supply chains: one with forced labour and one without. The forced labour-free supply chain may serve the U.S. market where laws such as the UFLPA ban on goods made with Uyghur forced labour, while the supply chain with forced labour would continue to serve markets less concerned about these practices or without comparable import bans.

Bifurcated supply chains allow forced labour to continue, and allow the companies to continue to benefit from forced labour without losing business. In some cases, a company may operate a bifurcated supply chain to avoid legal accountability under import bans such as the UFLPA. Bifurcation is seemingly happening in the solar industry with solar companies. There are reports that companies linked to Uyghur forced labour are building capacity and facilities outside the Uyghur Region, while maintaining operations in the Region, thereby in essence creating two supply chains. Some of the world’s largest solar module manufacturers have bifurcated their supply chains, developing alternative sources for polysilicon that they claim to have no exposure to the Uyghur Region. The same companies continue to source from suppliers or sub-suppliers that have exposure to the Uyghur Region for sales to other markets, which do not have forced labour import bans or other regulation to eliminate forced labour in supply chains

Companies should apply a single global standard, consistent with the requirements of the UFLPA, across their entire supply chain for all markets. Companies must also refrain from re-exporting any goods denied entry to the U.S. under the auspices of the UFLPA and attempting to sell in other markets. Efforts by civil society are focused on achieving comparable import bans that target Uyghur forced labour elsewhere including in the UK and Australia. An import ban on forced labour goods has been in place in Canada since July 1, 2020, and the European Union has proposed a trade and market ban on forced labour goods. These developments will make it harder for companies to maintain bifurcated supply chains and continue to sell tainted goods.