Stories of Uyghur Forced Labour

Numerous reports have highlighted the scale and forms of state-imposed forced labour in the Uyghur Region. Behind every report, there are individuals with families and friends, and communities being exploited and forced to work against their will. Learn about the experiences of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Kyrgyz who have been directly impacted by state-imposed forced labour in the Uyghur Region.

One Uyghur working at Yantai Longwin Food uploaded a video to Chinese social media asking, “Do you think there is love in Shandong? There is only waking up at five-thirty every morning, non-stop work, and the never-ending sharpening of knives and gutting of fish.” In another video at a fish packing line, one man asks “How much do you get paid in a month?” “Three thousand,” another responds [330 GBP]. “Then why are you still not happy?” “Because I have no choice.”

Over 1,000 Uyghurs have been forcibly transferred from the Uyghur Region to work in major seafood processing hubs in Shandong, China, since 2018. Thousands of Uyghur workers have uploaded similar videos of themselves at seafood processing plants in China on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, revealing the conditions at the plants. They appear unhappy and hopeless in the videos, sharing that they “have no choice” and work “non-stop.”

Gulzira Auelhan, a Kazakh camp survivor, testified she was detained in multiple reeducation camps and forcibly sent to work in a glove factory in Ili prefecture in 2018. She states she was threatened with detention if she refused to sign a one-year contract with the factory. Gulzira was told the gloves she sewed were made for international brands. "They told us openly that the gloves will be sold abroad, so we should do a good job.” The Yili Zhuowan Clothing Manufacturing Co. reportedly produces gloves worth over 11 million GBP per year, sold in the U.S., the European Union, Japan, and Russia. She states she was initially promised 600 RMB [x GBP] per month, less than half of the minimum wage, but was paid 10 Chinese cents (2 cents) per pair. Gulzira was only able to sew around 11 pairs per day, which came out to less than 6 RMB [0.67 GBP] per day. She was required to stay in a monitored dormitory three kilometers away, which she was not allowed to leave. She reports having to take 45-minute Chinese lessons after work daily.

In 2021, Erbakit Otarbay, a 49-year-old Kazakh camp survivor, testified that despite not knowingly committing any crimes, he was transferred to multiple prison and reeducation camps and forced to work at a garment factory near a camp outside of Tarbaghatay in 2018. Otarbay said he sewed unbranded school uniforms, factory worker uniforms, and repairman clothing. “Initially, we made pant belts. The stitches must be extremely straight. If we messed it up, we had to redo it. We tried this many times and finally learned to do [it] well. Later we sewed other clothes. For example, school uniforms, repairman clothes, factory worker uniforms. I sewed for about a month.” Otarbay stated he was not paid for his work.

Dina Nurbydbai, a Kazakh camp survivor, was previously the owner of the Nilqa County Aidai Tailor Shop and the Kunikai clothing company in Nilka County before she was detained in 2017. She was forcibly transferred to another camp where was ordered to teach workers how to sew school uniforms. She said “it was a huge place. There were so many women there. They were all like me – prisoners.” She worked from 8am to noon and 1:30pm to 6:30pm and spent the evenings in the dormitory studying Mandarin and CCP propaganda. She was paid 9 RMB [1 GBP] per month and reports the factory was divided into chin-height, locked cubicles, which held 25-30 people each. There were cameras everywhere, including in the bathrooms, and security guards monitored workers on the factory floor. Dina says “I felt like I was in hell. They created this evil place and they destroyed my life.” She adds “I worked hard for 10 years to succeed. I lost everything, including my health.”

Nursman Migit started working at the Jiashi Shengtai Knitting Factory in Payzawat, Kasghar prefecture, under a state labour transfer program in 2016, according to Chinese state media. Migit told Kashgar Radio and Television: “I was a little disappointed and wanted to go back [home]” when she first was transferred. She stated she was paid only 1,500 RMB [165.26 GBP] a month for two years, below the local minimum wage. She also stated she became a member of the Communist Party, which is a form of mandatory ideological training common in labour transfer programs.

Aldiyar (pseudonym) is a former detainee who was forced to work in a factory making clothes, gloves, and bags for low pay. “We went to a garment factory. We didn’t have a choice but to go there… The salary was low. It was impossible to take care of my family with the salary. The first month [we were paid] 200 RMB [23.57 GBP]…The factory was on the outskirts of the [redacted] county seat. Only ethnic minorities were working in the factory – Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Hui.”

Maynur was forcibly transferred from her home in Ketiki Village, Keriye, Khotan in the Uyghur Region with only a junior-high-level education under the state “surplus labour” program in 2017, according to Chinese state media. Although Maynur and her parents resisted the work placement, she was forced to travel over 1,500 kilometres away from her home to work in the production workshop at the Zhongtai factory in Urumchi. Maynur is shown weighing products in this photo from China News.

Over 5,500 individuals from the southern Uyghur Region were transferred to work at Zhongtai facilities in Urumchi, Turpan, Aksu, and Fukang between Spring 2017 and June 2021.

Ibrahim (pseudonym) was forced to work in a garment factory for two weeks after being released from a camp. He stated other workers there had been forced to work in the factory when a family member was detained in a camp. “They taught us how to sew clothes. And while we were having lunch I spoke with women and girls [who worked there] and learned that those women’s husbands or girls’ fathers were in a camp. That was why they were taken there. I learned that if one family [member] was in a camp you had to work so the father or husband can get out quickly.”

Hasan Imin is one of 560+ Uyghurs who were transferred from the southern Uyghur Region to work at Zhongtai factories in Urumchi in 2017. A Zhongtai publicity piece notes that Hasan repeatedly expressed wanting to return home, stating that his “most common words” when he first started at Zhongtai were “I want to go home” and “I really can’t learn.” The article reports Hasan continued repairing forklifts at a PVC workshop and was not allowed to return home. Hasan is pictured inspecting forklifts in this photo.

Zhongtai is a state owned company that produces the majority of PVC made in the Uyghur Region which accounts for 10% of the world’s PVC supply as of 2022. Its factory in Urumchi alone produces 700,000 tons of PVC each year.

Arzu (pseudonym) was transferred from an internment camp to another camp, where he was taught to sew for three weeks. He told human-rights researchers that he was required to live and work in a factory for several months. “I was sent to a factory for five months, to make government uniforms at first. Then we started making dresses. I worked for eight hours a day. I had one hour of exercise in the yard… I was allowed to call family and friends, but not people abroad… There was no physical inspection, but we were given phones and asked to install a police app… We worked five days a week. The salary was 1,620 RMB [190.87 GBP] a month… We were really ineffective. We didn’t know how to do it. They had some Chinese woman come in for one week to try to teach us.”

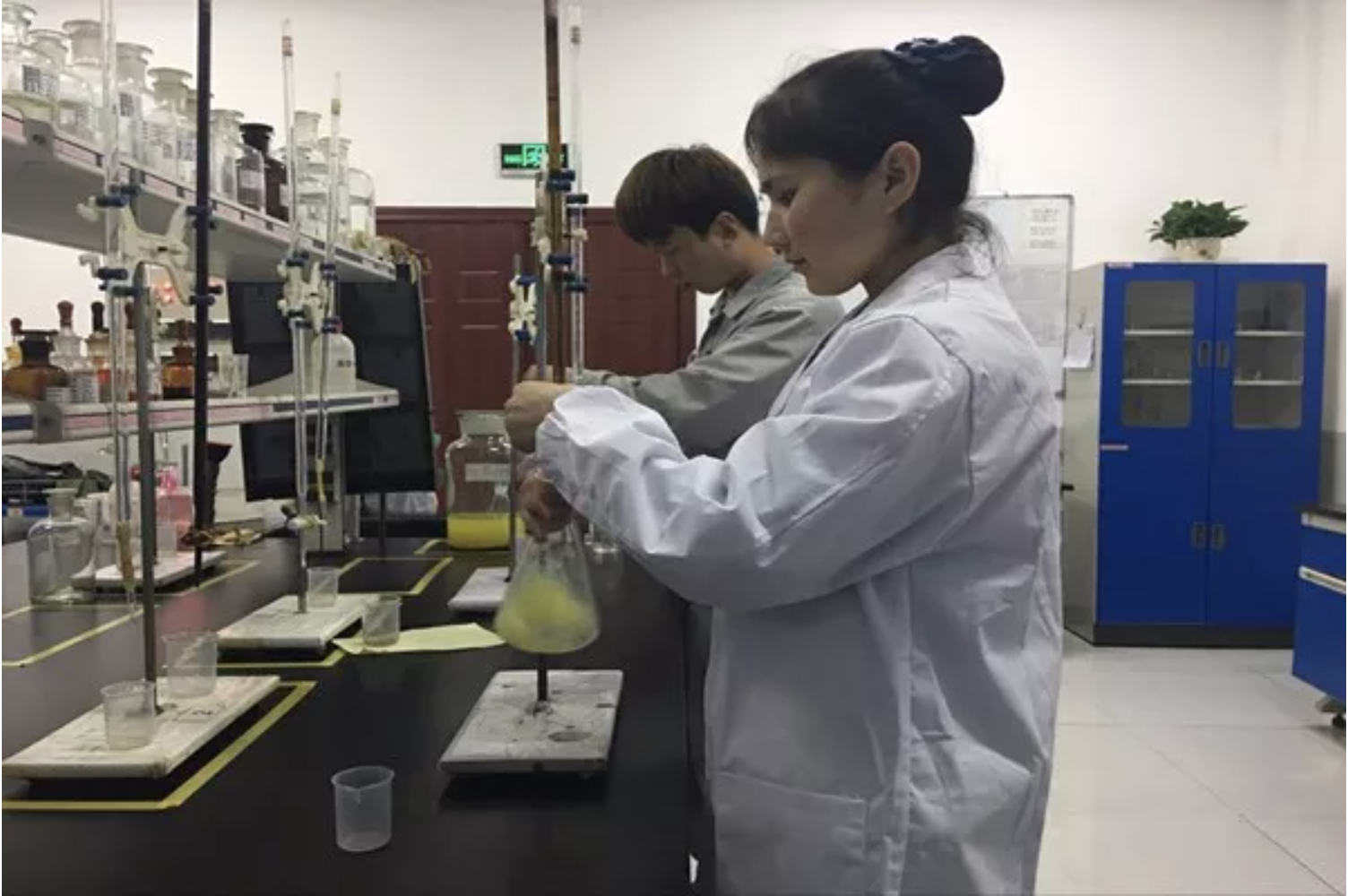

Rebiya Memet was in her early 20s when she was transferred from her home to work on testing products at Zhongtai Group’s subsidiary Mahatma Chlor-Alkali plant in July 2017, according to Chinese state media. Rebiya is shown testing chemicals in this photo here. Rebiya is among thousands of farmers who have been subject to mandatory ideological and vocational training and required to take an oath of gratitude to the company and the Chinese government.

Nursiman Abdureshid, a 33-year-old Uyghur woman, has testified that she witnessed nearly 100 Uyghur girls as young as 17 years old being forced to work at a textile factory in Jiangxi province in 2008. “I saw nearly 100 girls living in very old dormitories in the factory. And they said they do not want to work here. Most of the time they work in night shifts and sometimes they get so sleepy, and this causes their fingers to get injured by the machine so badly.” Abdureshid stated the girls were paid 25-35 RMB (2.95-4.12 GBP) per day and incurred debt to pay the factory for board and lodging. “In short, I witnessed the forced Uyghur workers’ unwillingness, and forced labour barely with no salary. Everyone felt like they were forced, and they were unwilling to work.They told me I don’t want to work, and some girls said they had to ask parents to send money so they could pay the factory. Some girls escaped and when they got to the train station the police brought them back.”

The Coalition wishes to thank the following for source materials and assistance: Amnesty International, Sheffield Hallam University Forced Labour Lab, and Uyghur Human Rights Project.

Video by the Ocean Outlaw Project. Photos by Kashgar Radio and Television, China News, Mahatma Chlor-Alkali, and Fukang Energy.